Within the inevitable tide of recognition of so many ladies artists of the previous twentieth century who handed merely as muses, lovers, wives or companions, when their work was actually as robust, stunning and unique as that of their companion, Dora Maar, for a lot of causes, occupies a particular place.

Maar was born Henriette Théodora Markovitch in Paris in 1907 and died on 16 July 1997. Her mom was a provincial, Catholic Frenchwoman and her father was an exiled Croatian architect who carried out necessary works in Argentina — the place they ended up residing for 20 years — however who by no means succeeded financially.

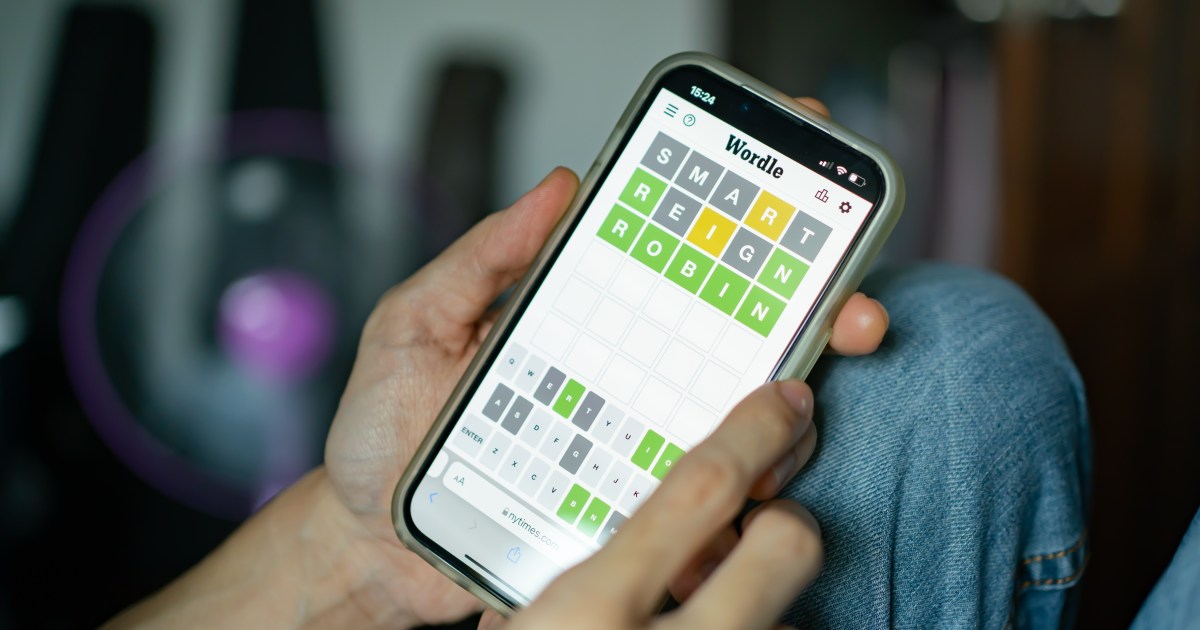

Maar Finds Pictures

![]()

When the household returned to Paris, Maar studied portray and ornamental arts earlier than making the digital camera her technique of livelihood and inventive expression. Vogue images, uncommon portraits – her output was so wide-ranging that in 1931, earlier than she was even 25, Maar already had a profitable studio alongside the set designer Pierre Kéfer.

Maar then opened a solo studio the place she created a few of her most well-known and delirious photomontages. The most effective recognized is maybe Ubu Roi (1936), the illustration of a wierd, non-human creature, a type of armadillo fetus — she by no means needed to point which animal it was in order to not lose its thriller — which André Breton thought-about an ideal instance of objet trouvé (readymade).

Additionally 29 rue d’Astorg (1936) is a transparent instance of surrealist images, wherein parts of various measurement, location and actuality are combined, as is Star Model (1936). Different photomontages of kids and ladies misplaced in limitless labyrinths or of bourgeois rooms invaded by mud and rain are additionally to her credit score.

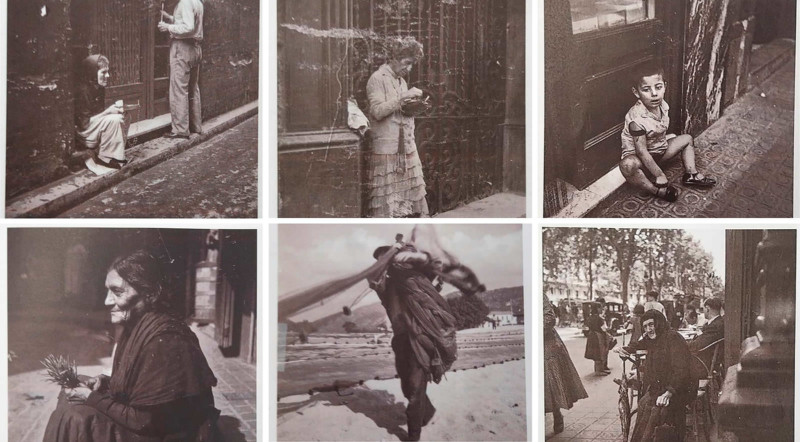

Within the first half of the Thirties, Maar, like fellow photographers akin to Henri Cartier-Bresson, alternated her depictions of the wealthy and well-known, trend and luxurious, with depictions of the squalor and poverty that existed in Paris on the time. The distinction between Maar’s images at the moment and people of Brassai, Eugène Atget and others is that the target or documentary facet doesn’t prevail in them, however relatively a seek for symbolism and freakishness that we might later discover within the work of photographers akin to Diane Arbus.

In 1932, Maar traveled to Barcelona and photographed avenue life within the metropolis. She additionally took crude portraits of poor folks.

Her work attracted the eye of the society of the time. She was quickly invited to affix probably the most superior and trendy circle in Paris: the surrealists. On this atmosphere, she was a lover of the author Georges Bataille, buddy of Jacques Prévert and Paul Éluard, and a detailed buddy of André Breton’s second spouse, Jacqueline Lamba. Actually, Lamba and Breton most likely met by way of Maar.

Surrealism freed Maar from the tyranny of appearances in images and allowed her to specific a wild spirit that mocked all the pieces, together with, and maybe above all, her personal fears.

Enter Picasso

Maar met Picasso in 1935, a yr earlier than the outbreak of the Spanish Civil Struggle. Along with her bodily and mental splendour, the Malaga-born artist was undoubtedly attracted by the truth that she spoke excellent Spanish.

Married to Olga Jojlova and likewise paired with a younger lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso fell head over heels in love with Maar. She had caught his eye by taking part in at reducing herself with a knife in a café and the painter stole the bloody glove she was carrying on the time. This, little doubt, was the start of a relationship with darkish omens.

When she turned a part of Picasso’s unusual circle, his circus of worthwhile however submissive girls, her profession ventured down a harmful path.

She spent eight years with Picasso. It was undoubtedly a rare interval for the artist, throughout which he painted lots of his greatest works, together with portraits of Maar. She carried out a rare act by photographically recording the constructive “course of” of Guernica. This was completely progressive on the time, and would give rise to many different works by photographers akin to Hans Namuth with Pollock, or Clouzot with Picasso himself, however Maar’s originality stays unrecognised.

Picasso additionally labored portray on negatives with Maar, however later insisted that she abandon images to dedicate herself to portray – in his view the “nice artwork”. On the finish, Picasso led Maar into the terrain he completely dominated.

It should be stated that she struggled to make private items and a few of her works, regardless of the affect of Picasso’s artwork, are attention-grabbing in their very own (e.g. The Dialog, from 1937). However to compete in a terrain wherein Picasso was the grasp was an virtually unattainable problem.

In 1945 Maar produced nonetheless life work within the type of Picasso and later some portraits, primarily of ladies, paying homage to different surrealist artists akin to Leonor Fini.

As at all times with Picasso, it was a brand new love affair, this time with the younger painter Françoise Gilot, that ended a relationship that had grow to be terribly poisonous, with Maar bordering on insanity and Picasso abusing her appallingly.

Third Act

Maar was confined to a psychological hospital, acquired electroshocks and suffered the horrible psychological remedies of the time, which was pretty much as good for schizophrenia because it was for damaged hearts or despair. Due to the poet Paul Éluard, who requested Picasso for assist, Maar managed to depart the establishment. She underwent remedy with Jacques Lacan, then went into seclusion, devoted herself to portray and sought reduction in a Catholic mysticism. Thus her well-known phrase was born: “After Picasso, solely God.”

From the Fifties onwards her portray moved in direction of abstraction, albeit intently linked to landscapes, extremely impastoed works which might be an entire departure from Picasso’s artwork however not formally very attention-grabbing.

Maar’s super emotional dependence on Picasso, the intense facet of her despair, meant that her determine, for a very long time, was disadvantaged of the brilliance that accompanied her early success and the complexity of her work.

Notable historians akin to Mary Ann Caws and Victoria Combalía, who knew her personally, introduced her out of anonymity with their writings. And little by little, exhibitions, such because the 2019 present on the Tate, have recovered her identify and her legacy for the historical past of artwork. The third act is underway.

In regards to the writer: Amparo Serrano de Haro is an Affiliate Professor of Artwork Historical past at UNED – Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. The opinions expressed on this article are solely these of the writer. This text was initially printed at The Dialog and is being republished underneath a Inventive Commons license.